The End of Pharmacist Final Checks

Any mistake made in the pharmacy can be a serious concern. Something as simple as attaching the label on the wrong drug can have profound consequences. Over the years there have been many well publicised cases where a dispensing error has gone on to cause serious harm, and in some cases death, to a patient. A quick Google search will return countless news articles of lives being destroyed by a single incident that can be traced back to a human error at the pharmacy.

The rate of actual dispensing errors varies between 0.2% and 3% nationally depending on which report you read. Whether or not we agree on the actual number, we can all agree on their significance. Dispensing errors don’t just cause harm to the patient. They can damage the reputation of the pharmacy business and potentially end the pharmacist’s career.

Until recently, a dispensing error causing the death of a patient was deemed a criminal offence and there have been high profile cases where pharmacists have been handed jail terms for fatal incidents. In 2018, after several years of campaigning, the law was finally changed to decriminalise dispensing errors but this does not mean that pharmacists can get away scot-free. Errors reported to GPhC may result in Fitness To Practice cases and at the very least the psychological trauma of an incident will weigh as heavily on a pharmacist as it does on a patient and their family.

The Final Check

For years, the pharmacy professions defence against dispensing errors has been the Final Check. It is the critical step in the dispensing process before the patient’s medication is bagged and handed out. It is the last opportunity for pharmacy staff to catch an error relating to quantity, strength, expiry date, or dose before it leaves the premises and potentially goes off to harm a patient.

The Final Check is the reason we see pharmacists waving boxes around in the air followed by a scribble in a box where it says “checked by”. In our fight against dispensing errors we see pharmacies plastered in posters highlighting the most popular “Look Alike Sound Alike” drugs that staff need to watch out for. We see pharmacies buried with SOPs meticulously setting out step by step how to check a labelled item.

But if this is our defence, then I would argue it’s pretty weak. These measures were never going to eradicate dispensing errors. They tick a box to show our regulators that we are exercising our professional responsibility. At best these processes might even capture a few errors up to the point of labelling, but still don’t stop mistakes that happen after this step such as packaging errors or handing out the whole supply to the wrong patient.

Delegating final checks to ACTs has helped remove some of the pressure from the pharmacist in busy pharmacies. However, this has not reduced the risk of errors given that any human is just as likely to make a human error no matter how vigilant they try to be.

So is this it? Is this the best we can do as a profession to ensure patient safety?

Advent of Technology

Titan PMR created a digital workflow that allowed the pharmacist to carry out the clinical check up front and all remaining steps to be carried out using barcode validation.

After the pharmacist has cleared the prescription for dispensing, a picking sheet tells the staff what stock to get. During the labelling process, the manufacturer's barcode is scanned. If the scanned product is the correct drug, correct strength, correct quantity and correct date, then a dispensing label is produced. If not, then no label is produced but a near miss is recorded.

Likewise, when it comes to packaging the dispensing labels are scanned one at a time before a bag label is produced ensuring that there is no mix up between patient’s drugs.

When it comes to handing out, the package label is scanned to ensure that the right patient is verified before the package is transferred to the patient.

This digital workflow has enabled pharmacies to operate the dispensing process without the need for any Final Checks except for split packs, controlled drugs and other high risk drugs.

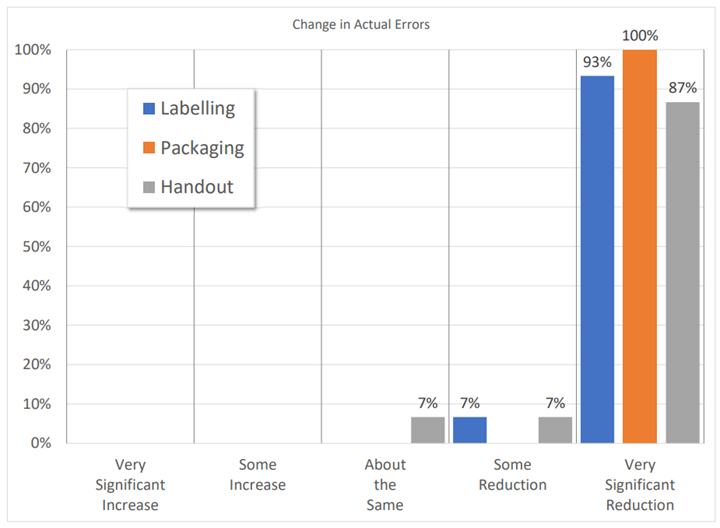

In a survey of 30 Titan pharmacies, who had been using the system for over a year, they compared their experiences of the barcode validation approach with their previous traditional final check process and the results have been quite remarkable.

The graph shows that 100% of users reported a Reduction or Very Significant Reduction in Actual Labelling and Packaging Errors (i.e. those that leave the pharmacy). 93% also saw a reduction in Handout errors. On average the pharmacies reported a 90% reduction in actual errors between Pre and Post Titan implementation.

The Future of Final Checks

Let’s face it, the Final Check, whether carried out by a pharmacist or ACT, is a consequence of the manual processes we have inherited from the days of FP10 paper prescriptions and traditional PMR dispensing processes. Contrary to popular belief, the Final Check is not a defined term in the Medicines Act 1968, but rather the only way we could think of to ensure the final supply matched up with the initial prescription.

In the last 10 years pharmacy dispensing volumes have increased by 25% alongside the addition of new roles and services now being offered by pharmacists. This has added considerable pressure and distractions on already stretched teams who are expected to continue supplying medicines without making a single mistake.

The concept of old school scribbling on labels and relying on the vigilance of pharmacists or ACTs at the end of every transaction is no longer a sustainable model to ensure patient safety. The advent of EPS and new technology has given us an opportunity to reconsider the whole process and introduce an end to end digital workflow utilising barcoding to validation each step of the way, helping us address packaging errors and handout errors as well as dispensing errors.

I believe the Final Check has had its final day and as a profession we should consider making barcode validation a mandatory process in every pharmacy. Surely, the evidence speaks for itself.